One of the things I do to put food on the table, both figuratively and literally, is write for a great magazine called Growing.

An article in a recent issue of the magazine deals with an issue of profound environmental significance. Controlling insect pests, unwanted weeds and pathogens by natural means should be the first line of defense, worldwide, against the predations of those organisms preying on the foodstuffs we all need for survival.

While the pop-environmental movement gets silly regarding the use of chemicals to control pests – mass starvation would accompany the banning of chemicals just as mass deaths as the result of banning DDT occurred in the 20th Century – the overuse or unnecessary use of chemicals leads to serious consequences.

At any rate, the following is the first part of the article now available at Growing Magazine. The entire piece is available at: http://www.growingmagazine.com/article-9288.aspx

|

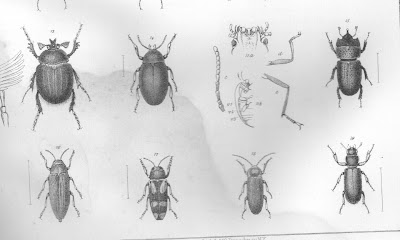

| Insects found and recorded in the 1850s during the exploration of the American West. Some are beneficial, some are not. Overuse of chemicals can impact both good and bad bugs |

Biological control of weeds, plant diseases and insect pests, according to Tony Shelton, Professor of Entomology at Cornell University in New York State, is defined as the use of predators, parasitoids or pathogens to reduce pest populations. Such agents are commonly called natural enemies. On the farms and in the forests and grasslands of America today, Dr. Shelton says, “While biological control will not solve all our pest problems, it should be a recognized component of any integrated pest management program.” Especially regarding farms, Dr. Shelton continues, “Both small and large scale farms can use biological control to reduce traditional pesticides inputs and make the systems more sustainable and less likely to experience pest outbreaks.”

Why Biological Control?

Some hear a term like “biological control” and automatically dismiss the concept as representing exotic, and narrowly applicable approaches to controlling plant and insect pest populations on farms. In fact, biological control has been a part of agriculture since the beginning of recorded time. Advanced biological control using techniques made available by modern science have seen increasing importance in America, and elsewhere, for as much as a hundred years. A 2008 paper by Dr. Shelton discusses a natural bacterium commonly called Bt, a biological control important to the nation’s corn and cotton industries. “Bt,” Dr. Shelton wrote, is, “One of agriculture’s best defenses against plant-eating insects…(Bt) can be sprayed on the surfaces of crops to provide temporary protection or can be genetically engineered into the crops to protect against insects throughout the lifespan of the plants. Bt has allowed growers to avoid applying large quantities of much “harder” insecticides.”

Biological control technologies are also seeing increasing importance as the move to organic farming gains momentum but, beyond organic farms, Dr. Shelton puts forward, “Biological control is an essential component in all cropping systems in use today, but is more effective in some than others. It is most effective in perennial systems like citrus and forests and in greenhouses, but natural enemies help suppress pest populations in virtually all systems.”

The natural enemies Shelton speaks of include predators, like lady bugs (lady beetles), who consume other insects over their lifetimes, parasitoids, species like some wasps that in an immature stage develop on or inside an insect host and, pathogens, disease causing organisms including bacteria, fungi, and viruses.

Biological Control as part of an integrated pest management system

In promoting biological control of the various pests bedeviling farmers and foresters Dr. Shelton is not suggesting the adoption of a wholesale switch to biological control. He is promoting the idea that biological control is a pest reduction strategy capable of enhancing the effectiveness of other approaches, reducing the negative aspects of a pest control regimen based strictly on chemicals and, important to any agriculturalist, improving profitability.

According to Dr. Shelton, effective management of insect pests rarely relies on a single control practice. Instead, a variety of tactics can be used as part of an integrated pest management (IPM) system to attack the problem of pests preying on valuable crops. “The goal of IPM is not to eliminate all pests,” Dr. Shelton continues. “Some pests are tolerable and essential so that their natural enemies remain in the crop. Rather, the aim is to reduce pest populations to less than damaging numbers. The control tactics used in IPM include pest resistant or tolerant plants, and cultural, physical, mechanical, biological, and chemical control. Applying multiple control tactics minimizes the chance that insects will adapt to any one tactic.”

Approaches to biological control of pests, insect and plant generally fall into one of three categories with considerable overlap at the boundaries of the techniques: conservation, classical biological control and augmentation.