If one really wants to do a bang up job of assuring we emit more carbon to the atmosphere, one should work hard to try to recreate an old growth forest.

In my corner of the woods a number of activist groups, individuals and other pop-environmentalists are trying to do just that as they struggle to convince policy makers to convert about 8,700 of working forest to park land today and, tomorrow, place additional tens of thousands of acres on the figurative chopping block.

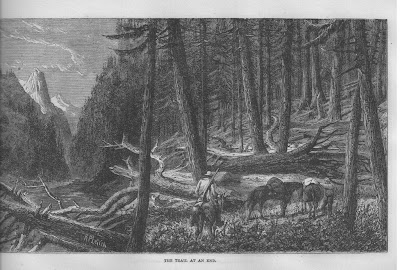

|

| An 1860s Rendering Of A Western Forest |

The activist’s approach is a great way to assure increases in greenhouse gas emissions to the atmosphere continue into the future. In addition to generally being less bio-diverse than newer forests (albeit old growth supports a different range of plant, animal and other life), old growth forests offer the advantage of lots of dead and dying trees rotting away to contribute the carbon they’ve stored to the atmosphere and, at some point, the likelihood they will burn and, in burning, will emit that carbon in a short term burst of CO2, methane, nitrous oxide and other gasses to what some claim is an atmosphere already overburdened by those compounds.

|

| Stereo View Of The Forest Near Mt. Hood Oregon - Late 1800s |

The Whatcom County effort involves removing a middle aged forest stand, a stand that is generally about 100 -125 years or so old, from the harvest cycle of a state agency charged with using the forest to provide funds for schools, libraries, port districts and local government.

The fetchingly labeled Lake Whatcom Forest Preserve Park is then to be essentially left free of the footprint of man, woman and child until it becomes an “Old Growth Forest.”

It should be understood that of Whatcom County’s approximately 1,400,000 acres, about 1,000,000 acres is already set aside as National Park, National Forest, State owned forest, private forest, and State and local parklands. About four acres of park exist for every man, woman and child living in the county.

The term Old Growth Forest should also be explained as it is a misnomer as used by the various activists interested in the new park.

A 50 - 100 year old stand of alder trees is an old growth forest. The older the stand the more likely most of the trees are beginning to rot or are already rotted at the core and likely to die within half the lifetime of the ordinary citizen.

When the pioneers began arriving in the western United States, a large variety of old growth forests made up perhaps as much as 15 - 25% of the forested area of the west. In some areas coastal redwood forests were predominant while in others the “old-growth” might be predominantly fir and/or cedar. Interior forests were heavily populated by species like the various pines, larch, or other species.

Something has changed in recent years. In decades past, old growth forests were defined by stand structure and the kinds of flora and fauna inhabiting the stands. Today, just as global warming has been replace by climate change by the spin doctors of the environmental movement, the terms traditionally defining old growth forest are changing. Stand structure and the inhabitants of the stand as definitional are being replaced by the number of years the stand has remained undisturbed. To the pop-environmental community old growth is defined by big trees and lack of human contact.

The pop-environmental community interested in the Lake Whatcom Park wants to recreate a particular kind of Old Growth Forest, one mostly based on the “new” definition as understood by the pop-environmental movement.

So what happens to a forest simply left alone to grow old and, eventually, die?

Well, as is the case with most life forms, nature is not very nice. In the natural world, most forests do not survive to reach “old growth” status.

|

| The Forest On Fire In The 1860s |

By way of example, the entire 8,700 acres contained in the Lake Whatcom Reconveyance burned sometime in the late 1800s. As is the case with most burned forests, pockets of the old forest survived the fire but, early photos of Whatcom County at the time and, the analysis of the forest by the U.S. Geological Survey in the last years of the 1800s demonstrates that most of Whatcom County’s lowland and foothills forests were thoroughly burned before the turn of the century in 1900. A huge part of Whatcom County’s forest products industry in the first decades of the 1900s consisted of cutting down burned trees and converting them to shakes and other products.

The Lake Whatcom forest is already known to have insect infestations. Across Washington insect infestations have reached epidemic proportions and are responsible for the intensity of some of the wildfire the state is becoming increasingly prone to so, it is at least a 50-50 proposition that fires will ignite in the new “park.”

Early settlers also reported massive blow downs of the original forest, ice storm damage and other natural occurrences.

So what happens then?

Well, if we are really trying to recreate what is in our mind, original conditions, we would let the forest incinerate when lightening or some other factor starts a fire. That then creates large areas of ash, tree parts and other materials that will fill streams for years and then, eventually, during the often devastating storms the county is prone to, will run off in the form of earth and debris slides ending up in the lake at the bottom of the hill where it will impact lake water characteristics for decades.

The burning forest also will pump huge quantities of greenhouse gasses and other chemicals into the atmosphere as it incinerates both endangered and not endangered species, boils water and elements like mercury out of the soil and, starts the natural process of reforestation over again.

The whole thing is, of course, a gamble. The future Lake Whatcom Forest Preserve Reserve Park could be the lucky one that doesn’t burn and, of course, those of us alive today don’t have to worry; we are gambling with the resources of future residents so we really don’t have to care what the odds of success are; it all makes us feel really, really, really good today and that is all that really matters.

A more logical thing to do would be to manage the forest for a variety of natural characteristics even as carbon is sequestered in the lumber taken from, for example, dead and dying trees removed to control severe insect infestations or root diseases or, whatever. Carefully done, forest management on an on-going basis allows for a full range of values to be realized from the forest. But it does have the downside of denying total control to those who constantly inform us they know best because they are the true “environmentalists.”